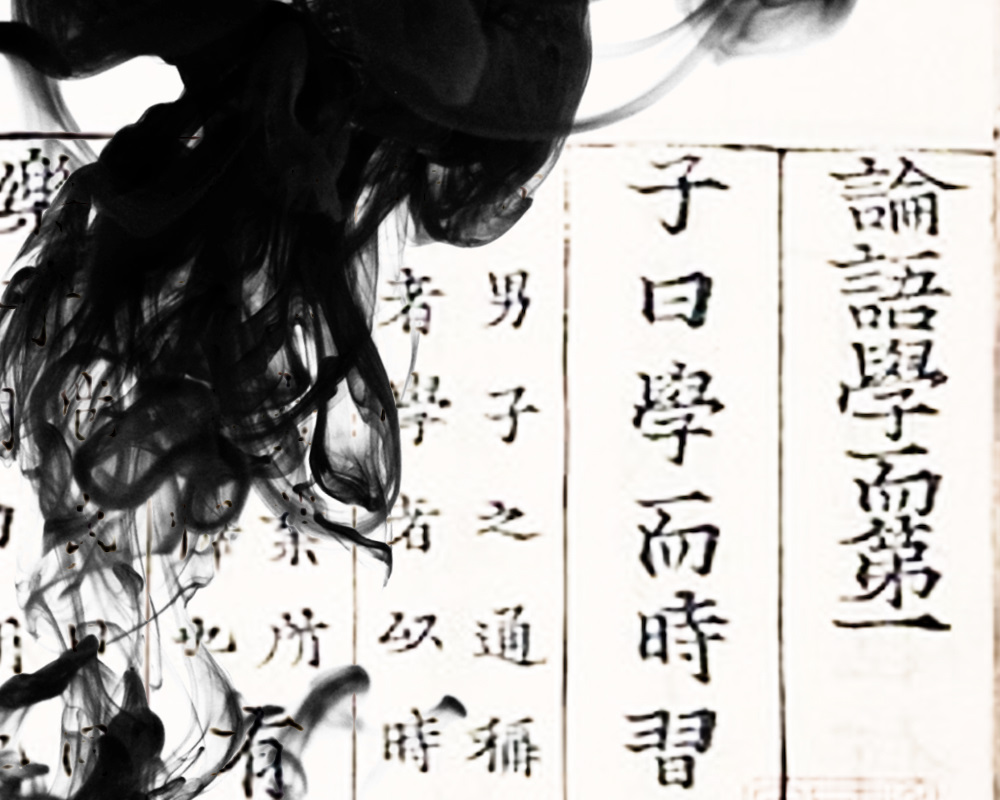

This time, I’d like to talk about The Analects, an ancient Chinese classic.

In Japan, most of us learn bits of it in our language classes at school. When I first encountered it as a child, I barely understood a thing. But now, reading it again in middle age, its depth leaves me speechless — the kind that makes you drift into a quiet daze before you even start thinking.

Words That Have Quietly Taken Root in Japan

Let me share a few famous lines from The Analects.

For those of us living in Japan today, many of these ideas feel so familiar — almost obvious — that we rarely stop to notice them. So this is a good chance to look at a few with fresh eyes.

故きを温(たず)ねて新しきを知る

―― By studying the past, we discover new insights.

おのれの欲せざるところ、人に施すことなかれ

―― If something would hurt you, don’t inflict it on someone else.

過ちて改めざる、是(こ)れを過ちと謂(い)う

―― The true fault lies not in making an error, but in refusing to amend it.

これを知る者は、これを好む者に如(し)かず。これを好む者は、これを楽しむ者に如かず

―― Knowing is good, liking is better, but taking joy in it is what leads you the farthest.

学びて時にこれを習う、また説(よろこ)ばしからずや。 朋(とも)あり、遠方より来たる、また楽しからずや。 人知らずして慍(いきどお)らず、また君子ならずや。

―― How joyful it is to learn and to keep learning.

How wonderful it is when friends who share your values come from far away.

And how noble it is to stay calm and unbitter even when your efforts go unnoticed.

My First Real Encounter with The Analects

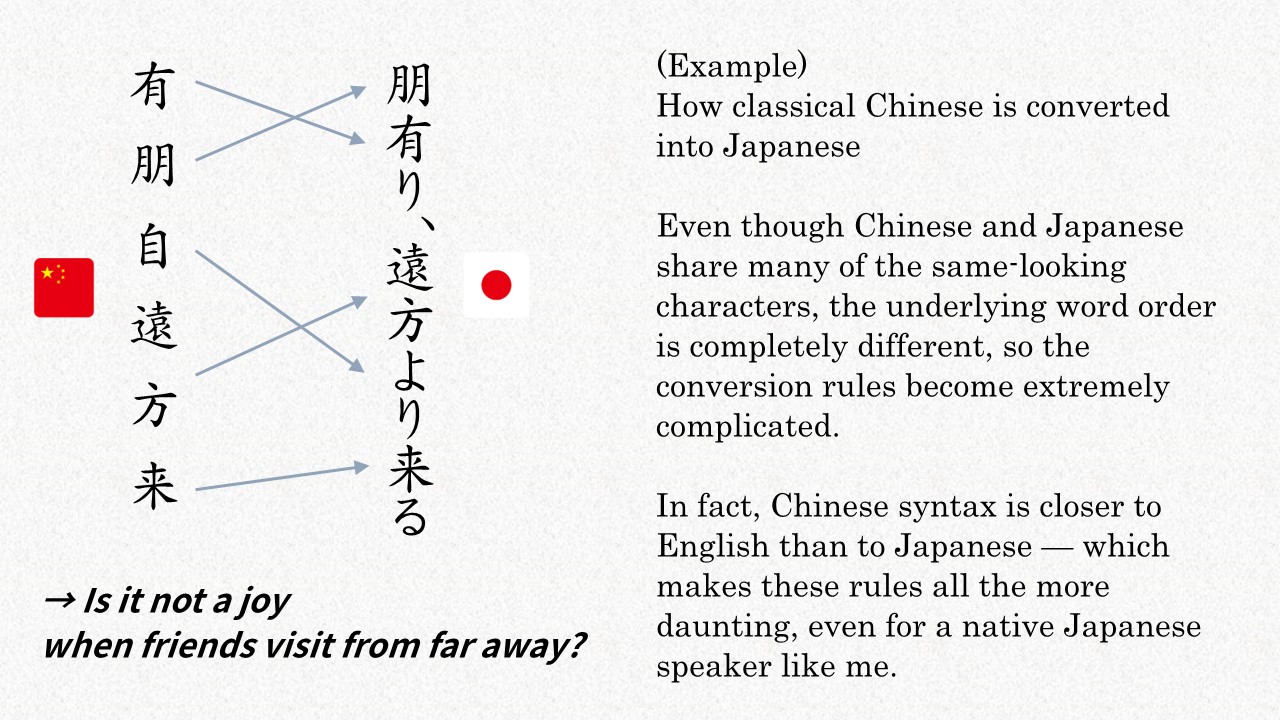

When you were a student, did you ever have to read texts that weren’t in your native language? And did you enjoy those classes?

As for me, even though I was in the humanities track, I really didn’t like them — honestly, I pretty much hated them. The texts we studied weren’t originally Japanese but ancient Chinese written thousands of years ago, and I couldn’t understand why we were supposed to learn them. On top of that, to read them “in Japanese,” we had to memorize all these strange rules, almost like decoding a secret code. I could never bring myself to like it. No matter what language you’re studying, I’m sure some of you reading this can relate 😌

I spent my school years disliking those classical Chinese classes, and when I finally graduated, I remember feeling quietly relieved — I’ll never have to study this again. Then more than ten years passed. One day, while wandering through a bookstore, a copy of The Analects happened to catch my eye. I picked it up without much thought, and to my surprise, it was fascinating. Yes, it was a modern Japanese translation, so of course it was easier to read — but more than that, the impression it left on me was completely different. The depth I could never sense as a child suddenly flowed into me, gently and clearly. I suppose that’s one of the small signs of getting older — and of growing a little as a person ✨

After that, I began reading other classics — the Chinese Cai Gen Tan, and Japanese works like The Manyōshū and The Pillow Book. And again, they were deeply interesting. It made me realize something: for children who have barely begun their lives, it’s almost impossible to truly understand or savor the meaning woven into classics like The Analects. Without lived experience, there’s nothing for the words to attach themselves to.

So if schools simply follow the old style of teaching without thinking about purpose or impact, the lessons won’t reach the students. They’ll memorize just enough to score well on tests, then forget everything the moment the exam is over. All that time and effort — gone. Looking back on your own school days — no matter where you grew up — I imagine many of you felt the same.

Now that I’m an adult, I can also understand the teacher’s side a little, so I can’t just criticize them. But when it comes to education, we really do need to keep asking:

- Why are we teaching this?

- What should students gain?

- How should we teach it?

- Does it fit the times?

Those questions never go away.

The Analects ⊂ Confucianism ⊂ Confucius

From here, let me share a bit about The Analects themselves.

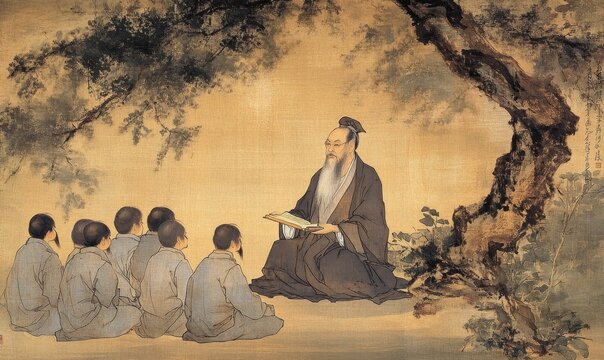

The text is said to be a collection of teachings spoken by Confucius, compiled by his disciples in ancient China. It’s astonishing when you think about it — the words of a man who lived thousands of years ago continue to shape cultures far beyond China, across places like Japan, Korea, and much of East Asia.

Let’s take a gentle look at how that came to be ―――

And even in the 20th century, although postwar reforms rejected many formal aspects of Confucianism, its values remained quietly alive — in ideas like courtesy, filial piety, diligence, and perseverance.

Life Lessons

To close, let me share one passage from The Analects that I especially love.

子曰く、吾(われ)十有五(じゅうゆうご)にして学に志す。

三十にして立つ。

四十にして惑わず。

五十にして天命を知る。

六十にして耳順(みみしたが)う。

七十にして心の欲する所に従へども矩(のり)を踰(こ)えず。

―― Confucius said:

At fifteen, I set my heart on learning.

At thirty, I found my footing.

At forty, I no longer felt lost.

At fifty, I understood the path heaven had given me.

At sixty, I could listen with openness and grace.

At seventy, I could follow my heart freely without stepping beyond what is right.

There’s a depth in these lines that moves me every time. They capture the milestones of a life with such clarity and calm, as if summarizing decades of growth in just a handful of sentences.

As for me, I’m now somewhere in the middle — at the stage of “no longer feeling lost.” To be honest, even past forty, I still find myself wavering. I’m nowhere near that level of clarity. And yet, compared with my twenties and thirties, I feel a bit more grounded — as if a quiet sense of conviction has begun to take shape.

I wonder how the years ahead will unfold. And I can’t help but hope that, step by step, I might grow a little closer to the journey described in these words 😌

That’s all for this article.

If you’re someone who once disliked classical texts in school — and perhaps still do — it might feel a little surprising, and there’s a whole new world waiting when you revisit them as an adult.