Another year is already drawing to a close.

Here in Japan, as the year-end approaches, the streets fill with the familiar scenes of bonenkai — year-end drinking parties held, quite literally, “to forget the year.”

But there were some days I didn’t want to forget at all.

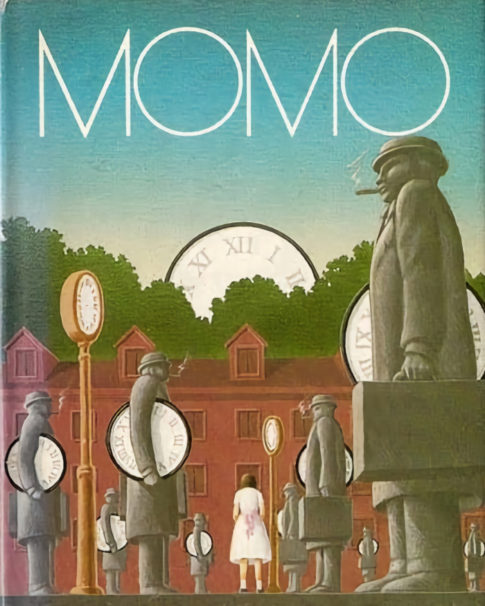

Today, I’d like to introduce a film that has stayed with me:

PERFECT DAYS

“There’s nothing interesting about my everyday life…”

“I’m probably no good anyway…”

For those kinds of days, when such thoughts quietly creep in, this film gently nudges you forward.

(“The world’s cleanest” in the title is, admittedly, just my personal impression…)

About the Film

Set in Tokyo, the film follows the everyday routine of a toilet cleaner, played by Kōji Yakusho, with restraint and simplicity.

At the Cannes Film Festival in 2023, Yakusho won the Best Actor award — becoming only the second Japanese actor to do so, following Yūya Yagira, who received the honor years earlier for Nobody Knows.

The director is not Japanese, but German filmmaker Wim Wenders. He is known to deeply admire Yasujirō Ozu (1903–1963), one of the masters of Japanese cinema.(Ozu’s Tokyo Story is a film I personally love as well)

Even a brief glance at this film makes it clear that it offers a perspective and style unlike anything we usually see. That, in itself, made me wonder:

Why was this film made in the first place?

Curious, I decided to look into its background.

The starting point was a project by The Nippon Foundation called THE TOKYO TOILET, an initiative to redesign public toilets across Shibuya. The project aims to present toilets as a symbol of Japan’s omotenashi — its culture of hospitality — to the world.

Originally, the idea was to document this initiative on film as a form of promotion. That plan eventually evolved into PERFECT DAYS. (Of course, the film goes far beyond being mere publicity)

Still Days

When the film ended, the first word that came to mind was “silence.” The protagonist — a man approaching old age and unmistakably introverted — speaks little, keeping his words to an absolute minimum. There is no television in his home. No smartphone. No background music added for dramatic effect. What we hear instead are the sounds of everyday life.

Leaves brushing against one another.

The soft click of a door opening and closing.

The shutter of a camera.

A can dropping from a vending machine.

From the quiet emerge countless small sounds we usually overlook — ordinary noises, gently rising to the surface.

The story itself is equally restrained, almost motionless. Living alone in an old apartment near Tokyo Skytree, the protagonist spends his days working as a public toilet cleaner. The film simply, steadily follows this routine.

There is no enemy to defeat.

No goal to reach.

Only the repetition of an unremarkable everyday life.

~ He leaves for work early in the morning, listening to his favorite cassette tapes as he drives. He carefully cleans each toilet, then eats a simple sandwich for lunch at a shrine. In the afternoon, he cleans again, finishes his shift, and heads home.

On the way, he stops by a public bath, then has a drink at a modest diner in the subway station. Back home, he reads in bed, and eventually falls asleep.~

I found myself genuinely impressed that a story with so little rise and fall could hold the screen for nearly two hours.

A Film Best Savored in Adulthood

If I had watched this film in my teens or twenties, I doubt it would have left much of an impression on me. At that age, I probably would have felt nothing at all. But now, having passed forty — at a point where life has begun to make a little more sense — the film quietly sank into my heart.

I often like to think of life as a mountain climb.

When we are young, it feels like an uphill journey from the foothills to the summit.

Relying on sheer energy, we push ourselves upward, and with every step, our view widens. We feel joy in our own growth, in expanding relationships, in first experiences and unfamiliar places that make our hearts race.

After forty, however, life begins to resemble the descent from the peak. The scenery feels familiar — much of it already seen on the way up. It is no longer about “going up,” but about “going down,” an act that carries a faintly negative image. Physically, too, descending can be surprisingly hard…

And yet, from above, a beautiful landscape spreads out below. We begin to notice plants and small animals we overlooked while climbing. With a little more room in our hearts, we may even find ourselves greeting strangers we pass along the way.

There are gentle scenes in the film where the protagonist brings home a small plant he has found, caring for it quietly, exchanges a simple game of tic-tac-toe with an unknown person using scraps of paper left in a toilet stall. These moments feel very much the same.

The latter half of life may be a downward slope, but it offers emotions we could never experience on the way up.

Life does not have to be flashy.

It does not have to be extraordinary.

There is something deeply satisfying about finding small joys in ordinary moments — a sense of quiet fullness.

It seems to me that this film captures precisely those subtle feelings that only adulthood allows us to recognize.

Komorebi

There is one image in this film that lingers in the mind.

During a break on a weekday, the protagonist eats his lunch at a small shrine. Fresh green leaves fill the space around him, and when he looks up, soft light filters through the trees — komorebi, gently swaying above.

That same image returns again later, appearing repeatedly in the dreams he has at night, as the day comes to an end.

After the end credits, these words appear on the screen:

“KOMOREBI”

is the Japanese word for the shimmering of light and shadows

that is created by leaves swaying in the wind.

It only exists once, at that moment.

The fact that these words are placed at the very end of the film feels deeply intentional.

If the many joys and sorrows we experience in life are like the light and shadows cast by komorebi…

When the wind shifts, light falls where there was once darkness.

And just as we begin to feel that warmth, the shadow returns again.

Time passes — fleeting, ever changing.

And because of that, I feel we should treasure every moment, whatever form it takes.

Those were the thoughts that came to me as the film drew to a close. As for what this film is truly trying to say — that is something I hope you will feel for yourself.

That’s all.

I wish you a wonderful day, and a peaceful year’s end and beginning.