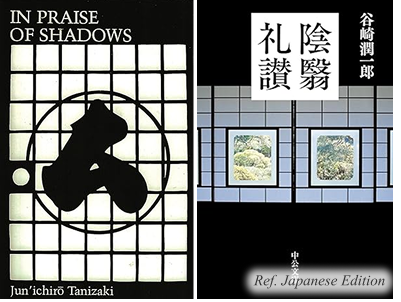

This time, I’d like to introduce In Praise of Shadows, an essay by the Japanese novelist Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, known for his elegant prose that explores human desire and beauty.

Born in the Meiji era (1886), Tanizaki is celebrated for works such as A Portrait of Shunkin, Naomi, and The Makioka Sisters. The Tanizaki Prize, named in his honor, remains one of Japan’s most prestigious literary awards, received by writers such as Shūsaku Endō, Kenzaburō Ōe, and Haruki Murakami. He was also the first Japanese author to be appointed an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Among his many works, I feel that In Praise of Shadows allows us to hear his voice most directly — not through fiction, but through his living thoughts and sensibilities.

The East, and the Japanese

Here’s a passage from the book that left a deep impression on me:

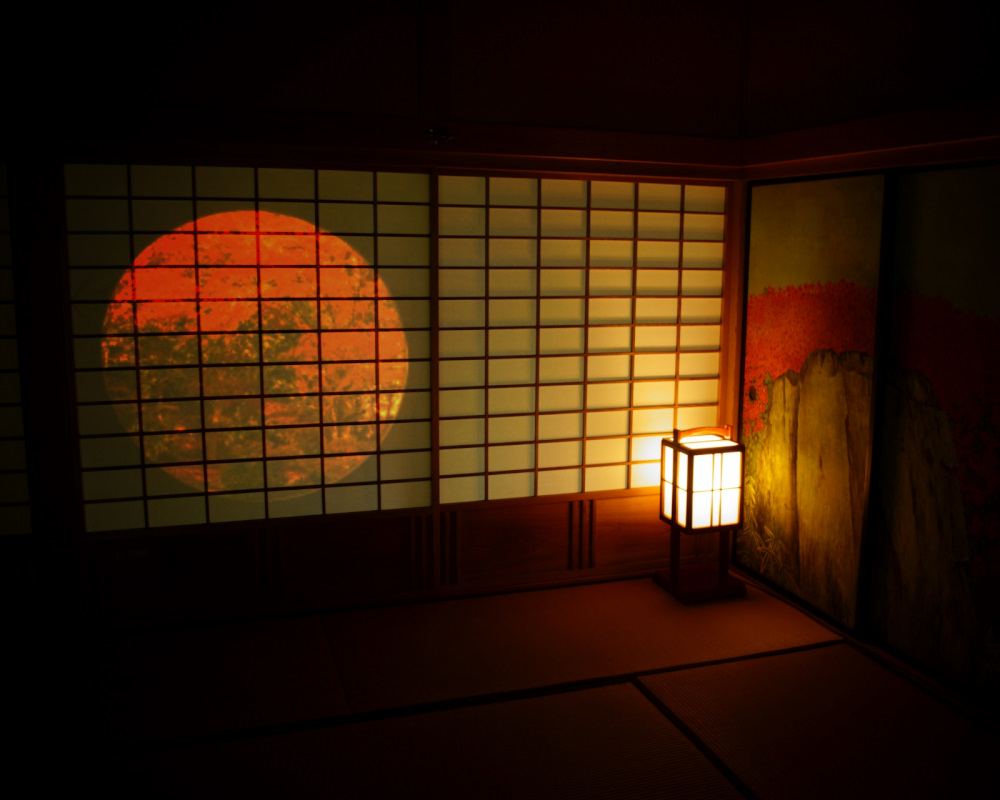

We Orientals create beauty by bringing a world of shadows into places where there is none. [・・・] Our way of thinking tends toward this: we believe that beauty does not lie in the object itself, but in the delicate play of shadows between things, in the harmony of light and darkness.

Just as a luminous pearl glows only in the dark but loses its charm when exposed to the full light of day, so too does beauty cease to exist once it is separated from the workings of shadow.

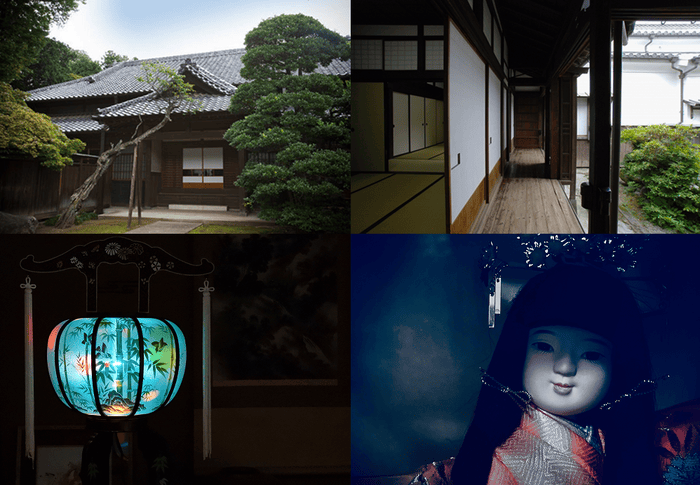

If we were to liken a Japanese room to an ink painting, the shōji screens would be the palest shade of ink, and the tokonoma alcove the darkest. Whenever I look at a tokonoma designed with refined taste, I am filled with admiration for how deeply the Japanese have understood the mystery of shadow, and how skillfully they balance light and shade.

For there is no special ornamentation there. It is simply a space divided by clean wood and unadorned walls, where the light that filters in creates soft, hazy gradients of dimness. [・・・] Even knowing it is nothing more than an ordinary shadow, one cannot help feeling that the air there has fallen into utter silence — that an eternal stillness reigns within that darkness.

The beauty of Japanese lacquerware, too, reveals itself only when placed in such faint, diffused light. At the warajiya tea room, a cozy space of about four and a half tatami mats, the pillars and ceiling shine with a dark luster, so that even a paper lantern gives off only a dim glow.

But when you replace it with an even darker candlestick and gaze at the trays and bowls beneath its flickering flame, you begin to see that their glossy, lacquered surfaces take on a new and deeper allure — like the quiet depth of a still pond. Then one realizes that it was no mere coincidence that our ancestors discovered urushi lacquer and grew so attached to the sheen and color it brought to the objects they crafted.

I wish to call back, if only into the realm of literature, the world of shadows we have already begun to lose. To deepen the eaves of the literary hall, to darken its walls, to press what is too easily seen into the dark, and to strip away all needless decoration within.

What do you think?

This book was published nearly a hundred years ago. Even back then, Japan was already under the influence of Europe and America — and that influence has only deepened over time. As a result, our homes, daily items, and lifestyles have changed dramatically from those days. But the influence has not stopped at material things — it may also have reached into our senses: the way we feel light and shadow, color and atmosphere.

If Tanizaki were to see modern Japan, I think he would be astonished — whether he approved of it or not (And I suspect he wouldn’t be the only one.)

Even so, I believe many Japanese people today, myself included, can still picture the world he describes. Some may even feel a quiet nostalgia for it. It’s strange, isn’t it? Those scenes have almost disappeared from daily life, yet they still live vividly in our minds. Perhaps it’s something engraved in our DNA as Japanese. And this longing for the old Japan — though faint when I was young — seems to have grown deeper and stronger with age, as the years quietly pile up.

Have you ever felt something similar about your own country?

Shadows and Shades

Here, I’d like to add a note about the Japanese word “in’ei” (陰翳) used in the original Japanese title.

Unlike the alphabet, which is phonetic, kanji are ideographic — each character carries a layer of meaning and emotion. Even when two words sound the same, the choice of characters can subtly change their nuance.

The word “in’ei” is usually written as 陰影, while 陰翳 is far less common today. At first, I thought Tanizaki simply used the older form of the same word — after all, he lived long ago. But it seems that’s not the case.

- 陰影

Refers to the shadowed part created when light falls on an object — the contrast between brightness and darkness. It emphasizes clarity and structure, highlighting form and depth. In Western art and architecture, it is often valued as a technical or aesthetic element that defines realism and perspective. - 陰翳

Describes gradations of light and shade, the subtle depth, mood, and atmosphere born from dimness. In Japanese culture, it carries aesthetic meanings such as quietness, mystery, and refined beauty. It is not merely the contrast between light and dark, but the inner richness that darkness brings — the realm of feeling and perception.

It seems there is such a difference between the two.

Incidentally, the house where I was born and raised was a rather traditional Japanese-style home — quite different from modern ones. There were no Western rooms; all were tatami rooms, and even the toilet was the old-fashioned kind 😅

That was several decades ago, and it might partly be because I grew up in the countryside. But nowadays, even when you visit your grandparents’ home in rural areas, houses like that have become quite rare, haven’t they?

I remember that there were always a few places in the house where sunlight didn’t reach — slightly dark corners. As a child, I sometimes found that darkness frightening. And of course, we had Japanese dolls on display. I can still recall the eerie feeling of their faces faintly emerging from the half-lit shadows・・・You know what I mean, right? Almost like a small haunted house 💧

But after reading In Praise of Shadows this time, I finally understood that such darkness had its own reason. Now, as an adult, I actually find myself comforted by a softly dim room rather than one glaringly bright. It feels calmer — like my mind can breathe.

Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba

Changing the subject a bit—

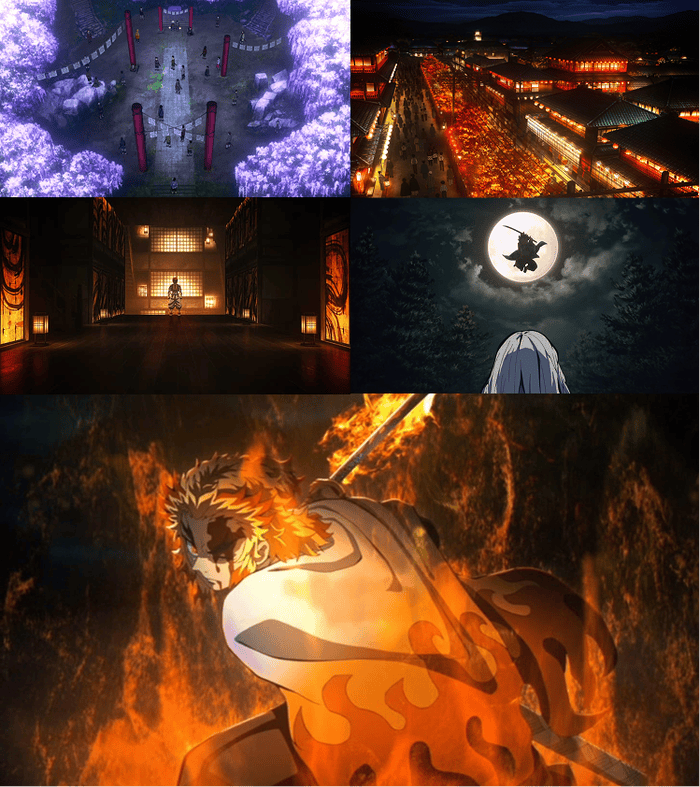

Do you know the Japanese anime Demon Slayer ?

It’s an enormous hit in Japan, and by now it has also gained wide popularity overseas, with theatrical releases around the world. I recently saw news that it became the highest-grossing Japanese film of all time, breaking numerous records.

For a long time, I dismissed it as something for children and didn’t bother watching it. But the social buzz became impossible to ignore, so I finally gave in and started watching it myself 😅

And my impression? — It’s truly fascinating!

I won’t go into the details of the story here, but the reason I bring it up is because this anime is, in many ways, filled with the very essence of “in’ei” — the world of shadows that Tanizaki wrote about.

The demons — the story’s antagonists — die when exposed to sunlight. Naturally, the tale unfolds mostly at night. The setting is the Taishō era, more than a hundred years ago, when electric lighting was still dim and rare. Streets and homes were wrapped in soft darkness. Within that darkness, the pale moonlight, the warm glow of old lamps, and the brilliant, stylized sword techniques of the characters stand out vividly. Together they create the world’s distinctive atmosphere.

And that darkness, I feel, isn’t merely shadow in the Western sense of contrast. It is 陰翳 (in’ei) — the Japanese depth of feeling, the quiet, profound beauty that lives within the dark.

Light, Shadow, and Us

From natural light to artificial illumination — if we look back through human history, it all began with the discovery of fire. Then came candles, lamps, electric bulbs… and finally, the LED lights that brighten our lives today. Through the control of light, human civilization has evolved dramatically.

But somewhere along that long journey toward brightness, we began to see darkness as something to be feared or rejected — something to be erased. And that view gradually extended beyond the physical world, into our spiritual one as well.

Yet it is precisely because there is shadow that light can exist.

And the stronger the light, the deeper the shadow it casts.

That is the law of nature — and lately, I can’t help but feel there’s a quiet lesson for us hidden in that balance.